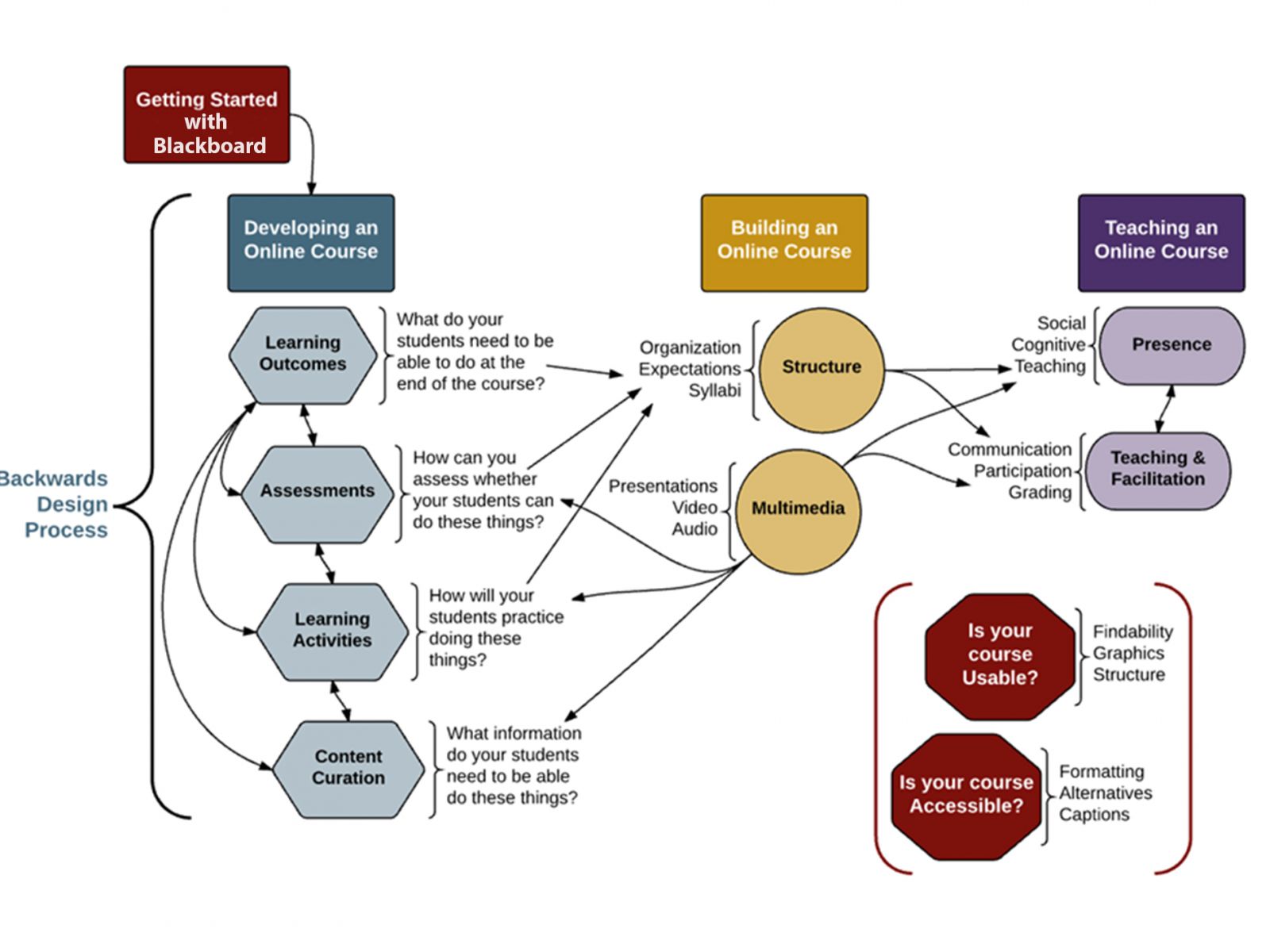

The Teaching Online Series is designed based on the principles of backward design, a very useful model for developing courses for both online and face-to-face settings. Wiggens and McTighe, in their book Understanding by Design (2nd Ed., 2005), describe the three steps of backward design.

Dee Fink (2013) describes the steps of backward design as making three key sets of decisions:

Alignment (Wiggens and McTighe) or integration (Fink) of desired learning outcomes, assessments, and teaching and learning activities provides consistency for students and supports more accurate construction of course concepts.

It's about beginning with the end in mind. Starting with desired learning outcomes, clearly stated in measurable terms, and working backwards through assessment activities, teaching and learning activities, and content delivery. In the following video, a University of Wisconsin faculty member describes how they are using the backward design process to improve courses.

Once you have a list of desired learning outcomes for your students you may see that you have more than is practical in a single class. This is quite common for outcomes related to content coverage. Fink (2013) identifies the heart of the issue as developing a "content-centered" course versus a "learning-centered" course.

A content-centered course is what everyone is used to - you were a student in them and you likely teach them as well. They start with a list of topics (not uncommonly based on textbook chapters) and work through them over the semester focusing on coverage. Alternatively, a learning-centered course begins with the answer to the question "What can and should students learn in relation to this subject?" and then move forward to organize activities, assessments, and content presentation in a way that supports that learning.

By starting from a learning-centered approach, it is easier to prioritize these content-oriented learning outcomes into three groups: the critical, the important-but-not-critical, and the nice-to-know. As you prioritize you will normally see a structure emerging that may not be in the same order or with the same emphasis as before.You will also likely see that there is not enough time to include all of the learning outcomes you have identified. Asking yourself questions like the following can help you sort and prioritize.

Once you have grouped and prioritized your outcomes you'll need to think about how to order them in the course. When you're doing this it's a very good time to also explicitly call out how the different concepts link together. These are the first steps to creating a course map. If you like to outline, you might find a table-style course map (doc, 17k) useful. As shown on the table, in addition to the following section on Learning Outcomes, the Assessments, Learning Activities, and Content modules will also include prompts to work on sections of your course map.

If you would like to see your course map graphically, Popplet and Lucid Chart provide free concept/mind-mapping tools. Below is an example using Lucid Chart to create a course map of the content for this course. A full map would also include the actual activities and assessments in context.