Resource pulled from: https://dillard.instructure.com/courses/3031/pages/2-dot-4-writing-good-learning-outcomes?module_item_id=37525

Learning outcomes guide your course design. They are the destinations on your course map. Once you know where you're going, the other questions, "How will I know when students got there?" and "What can I do to help them get there?" become much easier to answer. They are the formal statements describing what students are expected to learn in a course, whether for a classroom course or online. In short, they state where you want students to go (how they get there is the subject of later units). If you think of your course map as an actual map - outcomes are your destinations.

One of the major challenges of teaching online is that everything has to be more explicit than in a face-to-face course because the usual channels (your tone of voice, repeated vocal reminders, informal conversations before and after class) are absent. Online, learning outcomes express your expectations to your students. They are (hopefully) clear messages that help students know what you expect from them and what they should spend their time practicing and studying.

Learning outcomes focus on specific knowledge, skills, attitudes, and beliefs that you expect your students to learn, develop, or master (Suskie, 2004). They describe both what you want students to know AND be able to do at the end of the course. If you've not thought about learning outcomes from the perspective of what students should be able to know and do before, Angelo and Cross' Teaching Goals Inventory may be of help.

Learning outcomes need to specify student actions that are observable and measurable. That way they can be assessed in an objective manner. "Students will appreciate the beauty of impressionist paintings" isn't an effective learning outcome because it's not measurable. On the other hand, "students can identify impressionist paintings and accurately describe criteria for classifying paintings in the impressionist style" is a learning outcome because you can observe and measure the students identifying impressionist paintings and describing criteria.

In addition to being observable and measurable, learning outcome statements have to focus on student action. They are about students showing what they have learned, not about the instructor describing how they are teaching. For example, "The students can accurately describe the process of photosynthesis" is a learning outcome while "I will show a PowerPoint presentation on photosynthesis and give the students a quiz" is not.

Usage of the terms learning outcomes and learning objectives can vary considerably depending on the author; however, for purposes of this course, you may consider them synonymous (for consistency, we will be using learning outcome to reinforce the importance of observable behaviors).

In their basic form, learning outcomes are typically structured as

By the end of the course, students will be able to...[verb] + [object].

The place where learning outcomes often fall short is the verb, the action that students will do to demonstrate their learning. Often instructors use "know" and "understand;" neither of which are directly observable or measurable. Instead, consider verbs that can measure knowledge and understanding. For example, will students write, identify, or analyze something? Is it enough for students to be able to list the steps in the Krebs cycle or should they be able to describe the steps of the Krebs cycle? The decisions you make now have a significant impact throughout the rest of the course design process, so it's worthwhile to wrestle with the language to find the best verb to indicate what level of knowledge or skills you think students should have.

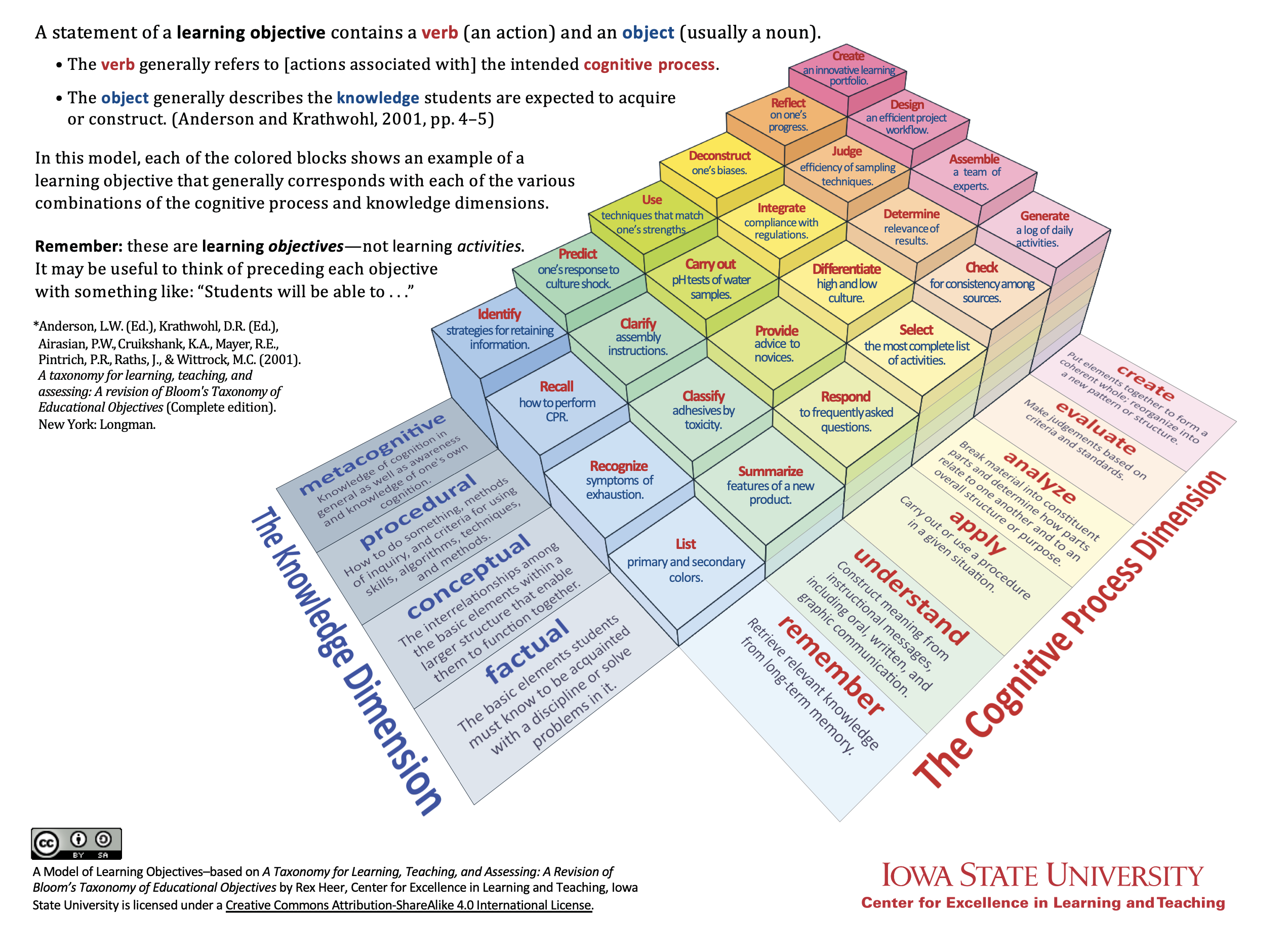

Many faculty members start their verb search with "Bloom's Taxonomy" (which was actually written by Bloom, Engelhart, Furst, Hill, and Krathwohl). The original taxonomy from the 1950s was revised in 2001. For information on the differences between the original the revised version, Anderson and Krathwohl - Understanding the New Version of Bloom's Taxonomy provides a nice description. Even though most instructors focus on the cognitive domain levels (Remember, Understand, Apply, Analyze, Evaluate, Create), there is a second axis to the taxonomy - the Levels of Knowledge. These include

Iowa State University's Model of Learning Objectives provides an interactive way to look at the intersection of the Cognitive Domain Levels and the Levels of Knowledge. If you'd like to review active verbs for learning outcomes based on Bloom's Cognitive Taxonomy, Azuza Pacific University provides a list of Bloom's Cognitive Taxonomy verbs (pdf, 47k).

In 2003, Fink (2013) developed a "Taxonomy of Significant Learning" which he used in tandem with his backward design approach. This taxonomy integrates cognitive and affective areas and adds a metacognitive component. His 6 types of significant learning are interactive but not hierarchical and would be used selectively depending on the learning outcome desired. They are:

Resource pulled from: https://dillard.instructure.com/courses/3031/pages/3-dot-1-aligning-and-developing-assessments?module_item_id=37529

Alignment between assessments and desired learning outcomes is foundational if your assessments are to be valid. Just like in a research study where you want to make sure that your research instrument is measuring what you want it to measure, by aligning your assessments to your learning outcomes you are making sure you are assessing what you want to assess. As we mentioned in the Course Planning with Backward Design, Biggs (2003) describes the constructive alignment of three components: (a) measurable, clearly-stated learning outcomes, (b) assessment tasks that allow students to show to what extent they have reached the learning outcomes, and (c) activities (including content and practice) that help students reach the learning outcomes. Assessments that are aligned with your learning outcomes provide dependable evidence as to how well students are reaching the desired outcomes.

Clearly aligning assessments to desired learning outcomes also reinforces to students what needs to be mastered and helps them track their progress in the course. Students pay attention to what you test. For example, If your intent is for students to be able to apply, critique, or evaluate, but your assignments and exams ask students to remember, identify, and describe, then your assessments aren't aligned with your desired learning outcomes. Asking students to describe a concept doesn't encourage them to evaluate the concept in context and doesn't provide evidence that they can evaluate the concept.

The intent of Backward Design is that assignments (and everything else) are aligned to desired learning outcomes instead of creating learning outcomes based on what you are assessing. Starting with assessments and extrapolating learning outcomes from them is the definition of "teaching to the test." This may be necessary if your course is preparing students to sit for a licensure or registry exam, but those cases are the exception more than the rule.

Just as you can't confirm a hypothesis without testing it, so, too, you can't confirm whether your students have achieved the course learning outcomes without some form of assessment. This is why assessment is the second stage of backward design - if you know where you want students to go (learning outcomes), you next need to decide how you'll know if they've gotten there (assessment). Assessment is that evidence.

Although the types of assessments that often first come to mind are a test, paper, or lab exercise, many other activities can be used for assessment, including portfolios, discussion forums, concept maps, diagrams, and presentations. Any tangible output from a learning activity can be assessed. Your choice of output—and the activity designed to generate that output—should be determined by your learning outcomes; this is just as true in the online environment as it is in the traditional classroom.

Formative assessment is designed to provide feedback to both students and instructors about how well the learning process is going. Examples of formative assessment include self-tests, think-pair-share activities, and other low risk assignments that allow students to demonstrate their knowledge, skills, and abilities.

Another option for formative assessment is to develop a larger, summative assessment and break it into smaller components that can be turned in throughout the semester. This allows you to catch and address misconceptions, challenge students’ early analyses, and provide the opportunity for them to revise and resubmit each piece in a unified whole at the end of the semester or unit.

Formative assessment options such as ungraded self-tests using the Canvas Quizzes tool, think-pair-share activities in discussion forums or group spaces offer ways for students assess their own understanding of course concepts. If you are interested in embedding some understanding checks in your Canvas pages, try Quizlet which can be added by going to Settings and then Apps in your course.

An often overlooked option for formative assessment is peer review and feedback. When adequately scaffolded, peer review and critique can be a learning activity for both the student giving and the student receiving the peer review. The Assignments tool in Canvas provides options for blind peer review, or you can set up a Discussion where students post their thoughts or explanations or examples and then provide feedback to the person posting immediately above them. Students can be split into small groups where they can share an initial draft of a paper or project, each student gives feedback to all the other group members, and then they work together to synthesize their best efforts into a group report. Using the Group spaces in Canvas allows the instructor to see all of the initial drafts and student discussions while keeping each group separated from the other groups.

Summative assessment is designed to provide evidence that students have achieved a learning outcome or otherwise gained skills or knowledge throughout the course. End-of-semester exams, projects, portfolios, and presentations are often used to summatively assess students' knowledge and skills. Courses that use a blend of summative and formative assessments provide more consistent support for learning than relying exclusively on a midterm and a final exam.

Final papers, projects, and portfolios have a variety of options in an online submission. It's easy to incorporate media into Assessments, Discussions, and Pages - both in project instructions such as presenting a video case for analysis, and in student work such as recorded presentations, interviews, and demonstrations. A videoconferencing tool like Canvas Conferences can be used for synchronous assessments such as oral exams in languages. Other tools such as WebEx, Zoom, or Google Hangouts record individual video presentations or interactions such as mock counseling sessions and other role-play scenarios which students can submit to an assignment or share in a discussion.

Authentic assessment asks students to demonstrate skills and knowledge by performing realistic tasks within the discipline. It provides opportunities to practice, consult resources, get feedback, and refine performances and products. Well-designed authentic assessments:

Authentic assessment commonly uses strategies such as case studies, simulations, consulting (where students work with real organization to explore a problem and recommend solutions that are evaluated by both the instructor and the organizational partner), internships, and service learning. However, depending on the discipline, authentic assessment can leverage simpler tools. For example,

Traditional assessment (defined mainly as discrete-item testing) tends to emphasize the development of a body of knowledge or skill. Does a student know the who, what, when, and where? Traditional assessment strategies are helpful when you want students to identify one best answer and/or target isolated skills in a concrete fashion.

Something to keep in mind is that assessment methods do not have to line up with assessment approaches. For example, multiple choice test items can be developed to draw attention to contextual factors in an authentic case. In the same way artificial and minimally contextualized cases can be used to identify who, what, when, and where without asking students two work with holistic, complex problems.

Online testing using the Canvas Quizzes tool provides auto-grading and auto-feedback features with a wider range of options than blue book or scantron testing. You can provide video, audio, and images as part of a question, and students can record or upload video, audio, and images as part of their answers. You can pre-set different feedback for different incorrect answers and even re-route students to a review page explaining the question in more depth.

However, there are also drawbacks. Many faculty express concerns about the potential for cheating in an online class. Where a faculty member might make one test and deliver it once in a proctored room for a face-to-face course, a similar fully online test may be delivered over time. Remote proctoring services are available to allow students to take assessments at any time using their own computer while proctors monitor and record their webcams, physical environments, and desktops. These services provide secure authentication to help ensure assessment integrity however they are not inexpensive.

If you do use online testing features, here are some options to consider: